The energy and process technology markets are changing. Renewables are no longer the quirky alternative source of energy – in a growing number of scenarios, they are the default cheapest source of power. However, they are intermittent and have higher (short term) variance in delivery than conventional oil and gas derived sources, and yet, traditional downstream processes remain fundamentally designed for around the clock operation. They are not suited for the more opportunistic power sources of wind and solar, or general electrification. This probably needs to change. There is an increasing desire to onshore the production of key commodity chemicals and secure sovereign supply chains which will require a more bespoke approach to manufacturing, electrification, and process design.

In short, there is an increasing fundamental need for innovation in the energy & process technologies markets to create new process technologies that are far better integrated with the sources of power available locally. Combined with the fact that the global demand for energy and basic chemicals continue to increase means that there are significant opportunities for teams and companies that can innovate more effectively than the competition and get a firm foot in the emerging new era of energy.

However, herein lies the challenge in a market full of risk aversion and a traditionally conservative, incremental approach to innovation.

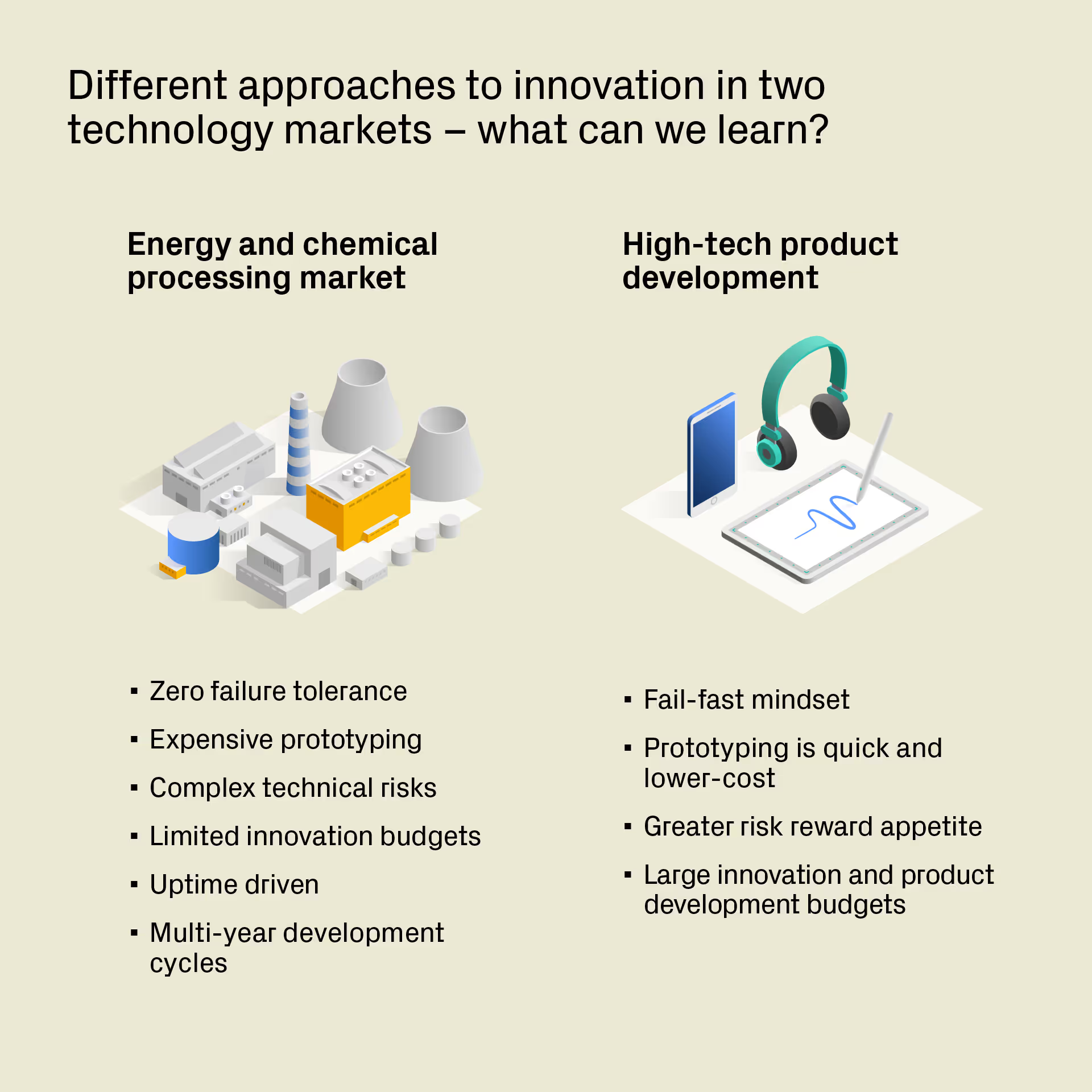

In the world of energy and chemical processes; fail fast is more like fail never, slow is the norm, prototyping is expensive, and technical risks are unacceptable. Failure is not an option, but the culture that has been designed to keep people safe and assets profitable over 30+ year lifetimes ultimately discourages the innovation that will secure the industry’s future. Furthermore, for decades regulators have been applying pressure to keep end-user bills as low as possible and in the process, have reduced the working capital available and stifled the appetite for innovation. Very few majors now keep a permanent staff of 100+ scientists & engineers in their R&D team as a result.

Yet, the energy and chemicals market is exactly that – it’s a market. It has customers, their demands change, competitors evolve, geopolitical events shake supply chains, nothing is static and not innovating is as good as moving backwards.

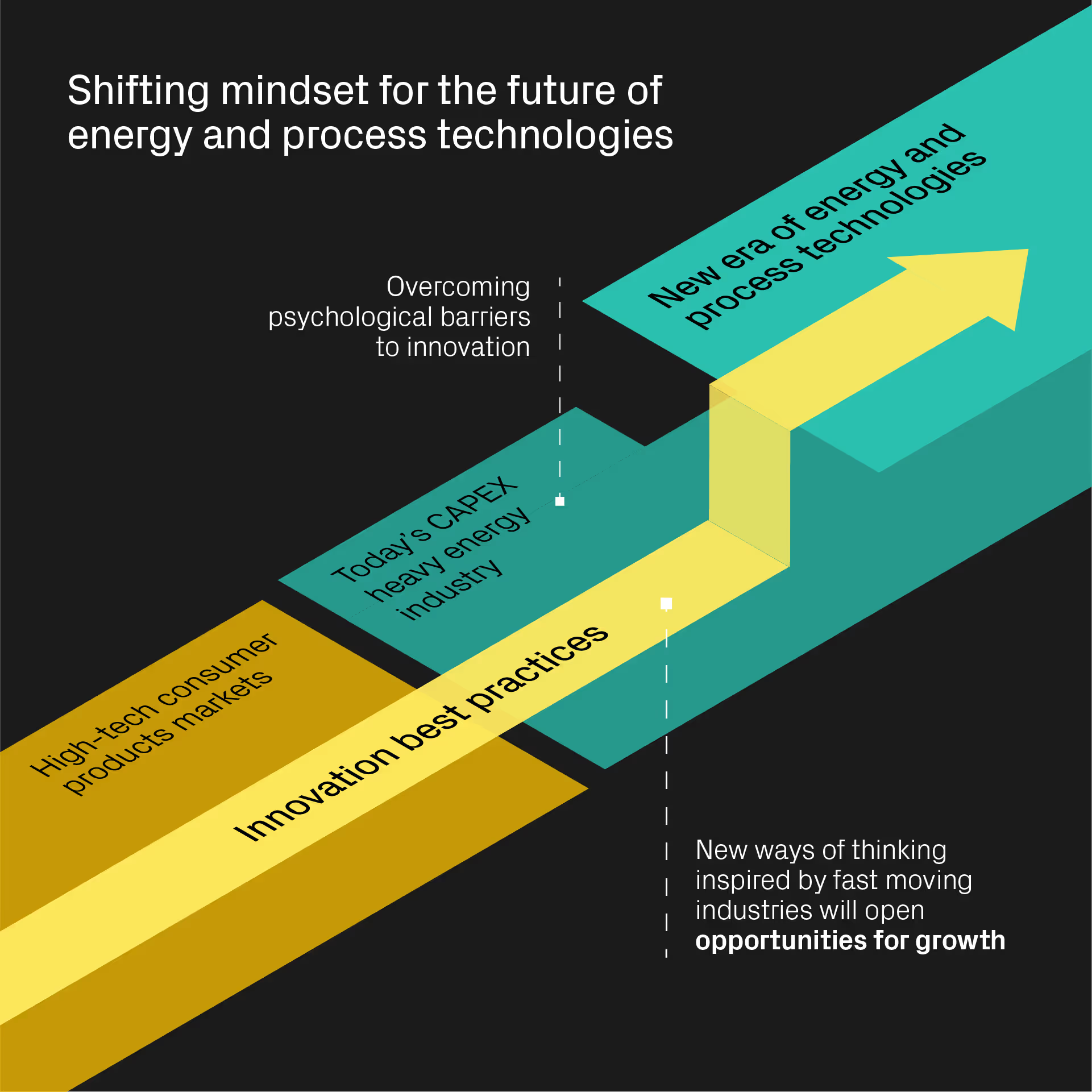

In this article, I explore another market which is far more accustomed to high-speed, disruptive innovation; to see if there are any changes in psychology which can be slowly adopted into the energy market and help companies to transition.

Which markets have a different innovation mindset?

It is worth quickly thinking about what the opposite looks like. For this purpose, the world of high tech consumer products couldn’t be any better. The key decision makers are the individuals, products are exchanged frequently, decisions are rapid and low-stakes, and individuals are heuristic, emotional beings. Innovating and trying new things is fundamentally expected and happens all the time. Iteration cycles are often on the order of months. The fight for rapid differentiation is intense, and billions of dollars are spent on creative agencies in an attempt to emerge above the noise. Products are often cheap and disposable - encouraging a fail-fast mentality. The rate of change can be mind boggling.

In our contrasting world of the energy market the key decision makers are large corporations, governments, plant operators, regulators, insurances, and specialist credit facilities. All with immense corporate inertia. The decisions are long-cycle, expensive, and high-stakes. Assets last for decades and everything accordingly moves more slowly.

The way individuals think in these two very distinct markets is different – and it is interesting to explore these differences purely from a cognitive perspective. There is much to be understood about the market and the psychology of innovation. Getting the balance right between the higher paced, higher risk mindset of consumer products; and the risk management orientated, conservative mindset of our world can bring value and longevity as the market continues to change. How can major players guarantee success as we move towards a new world energy order?

The psychological blockers of large infrastructure engineering

Here are some of the main institutional psychological repercussions of living in a CAPEX-heavy, long asset life, hazardous industry that I’ve observed over the last couple of years.

Loss and risk aversion

Engineers of large infrastructure instinctively overemphasise the potential downside of a new idea relative to its upside. Failures in their world can be catastrophic and this lies heavily on the mind. Rare catastrophic failure events last through living memory. As a result, psychological structures are erected to create a low tolerance for experiments that might lead to expensive reworks and cancellations.

Note that this is equally as pertinent from the commercial side as it is the technology/asset perspective.

Status-quo bias (the reliability paradox)

If something works, why change it? With typical asset lifetimes exceeding 30 years, you need to be sure it will work infallibly. If a design has worked well in the past, it is likely to do so again in the future. But for a new process or product – how do you know?

The mental paradox here is that longer something has been working for the harder it becomes to justify changing it. (Even though the older it gets, the riper it is for change).

Sunk cost fallacies

High CAPEX in new equipment encourages the mindset of “once you’re in, you’re in”. Let’s say you’ve committed $200m to a new furnace design and the performance isn’t quite as expected. Instinctively, you’d probably rather invest another $10m to try and make it work than throw the whole idea in the bin (even if there’s reason to believe it may never work).

Compare this to a new £10 widget – scrapping one of these and reworking an entirely new design is comparatively easy to reconcile mentally.

Uncertainty aversion

Projects & processes with incomplete data will get rejected, even if the expectation value is positive as the risk of uncertainty is too high. Compare this to the lower risk world of consumer products where, even with incomplete data a novel idea may just score a home run, meaning it is sometimes worth the risk of giving the new concept a go. The cost of reworking is lower and less capital needs to be committed to try – so why not.

In the energy and process market, this can lead to endless feasibility studies and an unnecessary level of modelling and fidelity required before moving forward with a decision. While the former is essential in managing risk and the latter a great way to reduce cost by simulating ideas in-silico, there can be a mental tendency to seek comfort in these activities at the cost of delaying affirmative decisions and losing commercial advantage.

Groupthink & safety in numbers

In such a high-risk game, making the same decision as someone else provides reassurance. Being bold or innovative requires bravery and most new ideas are often therefore quenched on day one.

Excessive academic curiosity

“Just give me 6 more months and I’ll find another 1% improvement”. Okay, this is more prevalent in the myriad challenger start-up companies we work with in this market. It’s a perfectly reasonable mindset for someone with an academic background, where it is in seeking these final 1% improvements that new science is sometimes uncovered. The challenge here is knowing when “enough is enough” and the leap out of the lab research into scale up and development is needed. Too many companies run out of time and runway trying to optimise everything in the lab before they even get to the engineering and scale de-risking stage. In the meantime, the company next door is moving to engineering, de-risking the actual hardware, and getting off-take agreements signed.

How do you create a culture of creative thinking, and step-change innovation that is also compatible with these incumbent psychological blockers?

In short – with difficulty. However, there are some ideas and mindsets that can be brought in from higher paced markets. In the right measure of course. Fortune does continue to favour the bold – especially in a quickly evolving geopolitical backdrop and when underpinned by an already solid corporate foundation. The value of innovation and developing new technologies continues to pay enormous dividends for our clients when done well.

Here are some observations of what works well and can be reasonably transferred from other markets that favour a faster innovation cycle.

Re-frame your baseline

Instead of only calculating an isolated ROI for a new product or innovative new process, compare it to the cost of not acting. Stranded assets, diminishing market cap, and the cost of not knowing (technology blindness). This helps with context and makes it easier to understand where risk-taking is necessary.

Industrial product development projects at TTP often begin with an early phase of work assessing the requirements and techno-economics of an idea. While it is a useful starting point to compare the new technology to “today” it is imperative that it is compared to the forecast in 5-10 years time when the new process or equipment will be expected to be on the market. Due to the speculation involved, multi-scenario and Montecarlo analysis techniques are needed.

Phased approaches and stage gates

Nothing new for managing projects with technical risk – but this needs to be designed and executed well to manage risk aversion and sunk cost fallacy pitfalls. Don’t just fail quickly – try and fail cheaply. Use sprint projects to make 80% of starting technical risks redundant before bringing in the engineering horse-power. If the concept can’t work – discover this quickly and cheaply, then move on.

Being able to take innovative risks while keeping the downside managed with smart programming can be an invaluable competitive advantage in and of itself. It puts you in control without slowing progress.

The FEL process commonly adopted in heavy industry is useful, and a fairly fail-safe way to manage risks for a large project. But being smart and spotting opportunities to reshape the process to your unique scenario, even bringing in other frameworks from (for example) product development, will generate small efficiencies that can result in a major competitive edge down the line.

Smart, surrogate experimentation

High‑reliability cultures reject experiments that threaten uptime of a major asset or value chain. Accommodate that instinct by packaging big ideas as a portfolio of small, reversible options that have no impact on the operation of large assets or products until the technical risks are removed.

Use surrogates where possible to keep the cost of testing down while still collecting the data needed to make a decision. This is especially powerful when combined with smart simulation and modelling activities. We recently completed an initial product concept phase of work for a client using plastic surrogate components in place of expensive nickel coated metal components. This allowed us to de-risk basic design features such as sealing and hydrodynamics early and cheaply.

Radical transparency and frequent communication

Keep your assumptions exposed, share negative results, and adjust the development course accordingly.

The fast follower approach

It is worth noting here that innovation doesn’t always come with the connotation of being the absolute first to bring a new technology or product to the market. Innovation is equally as effective at bolstering one’s ability to be a fast follower. The fast follower strategy is a sound one (and one which we observe many of our larger clients taking) so long as you are positioned to move rapidly once a change occurs. The risk of doing nothing is that you don’t develop the skills or foundational technologies to allow quick movement when the time is right. Therefore, well managed innovation is an effective hedging strategy to avoid obsolescence in a changing market when being a pioneer isn’t an option.

Summary

The energy market is changing at a pace perhaps last seen around 2008 with the shale revolution. This time, it is due to in an increasing rate of renewable assets being deployed as the lowest cost forms of power in many scenarios - leading to cheaper energy but with greater high-frequency variance. In an evolving energy market, the leaders of tomorrow will be the companies that not only come up with solutions to the laws of physics, but those that find solutions to overcome the laws of human psychology – laws that have been shaped by decades of a high reliability, high capex, low risk mindset – and integrate the right level of innovation into their organisation and product roadmaps.

While the conservative mindset is necessary to navigate the inherent risks of the industry, it is essential to identify when it is doing more harm than good. Keep it away from the exploratory innovative functions within your organisation, and recognise the long-term returns generated by advancing the technologies of tomorrow, today.

TTP is organised to create an environment in which these traditional blockers don’t stand in the way of innovation or slow progress. Used wisely, we unlock significant value for our clients by navigating the technical risks of new ideas and technologies quickly. Forming a team that becomes an agile, pointy, front-end extension to an in-house engineering unit that is experienced in finding and commercialising new technology opportunities. This function puts you in a position to capture the upside available in the changing market, while remaining in control and limiting downside exposure.

.avif)