Critical minerals are abundant. Profitable production is not.

Conventional critical mineral process technologies require an update for the geopolitical future of onshored supply chains.

Critical minerals are often described as scarce, strategic and indispensable, with demand accelerating as they become central to electrification, defence and critical infrastructure. But heavily concentrated supply chains dominated by China are causing significant price volatility for manufacturers in these sectors. Neodymium prices are up 95% YTD in response to the USA’s tariff wars, military action in Venezuela and desire for Greenlandic territory – echoing past shocks like China’s 2010 export halt to Japan that sent prices soaring ~10x in a year.

In response to recent events, governments, investors and industrial majors are again asking the question: how do we secure supply?

Yet beneath the longstanding concern that China has asserted a near-monopoly on critical minerals (especially rare earths) for decades lies an uncomfortable reality. Most critical minerals are not particularly rare. They are geologically abundant, widely distributed, and present in a number of waste streams, but typically only in low concentrations.

What remains genuinely scarce is a technoeconomic case that survives volatile payback over long asset lifetimes, and the valley of death between pilot and profitable production plant. This requires:

- Reduced capital costs of infrastructure and equipment

- Economically robust production routes that generate sufficient revenue without policy protection or artificial price floors

- Technologies aligned with UN sustainability goals

China has overcome the capital cost barrier to assert its supply dominance through decades of governmental strategic funding. The West is now taking a similar approach in its efforts to diversify supply chains, with public agency financing support for new mining offtake agreements and circular economy initiatives. However, in the context of geopolitical uncertainty, strong technoeconomics independent of pricing policy remain critical for private investor confidence.

Addressing these needs, innovations in chemical extraction are focusing on new opportunities in ‘unconventionals’ – alternative feedstocks beyond virgin ore that conventional technology can not economically process. Organisations that can translate these promising technologies from lab to market can harness abundant supply to meet rising demand, but success hinges on design choices grounded in technoeconomics and a clear route to market.

In this blog, we specifically focus on the future of rare earths, which represent the greatest challenges in geological concentration, technological dominance by China, and strong growth forecast driven by defence and electrification.

Rare earth ore reserves are known, but commercially difficult to extract

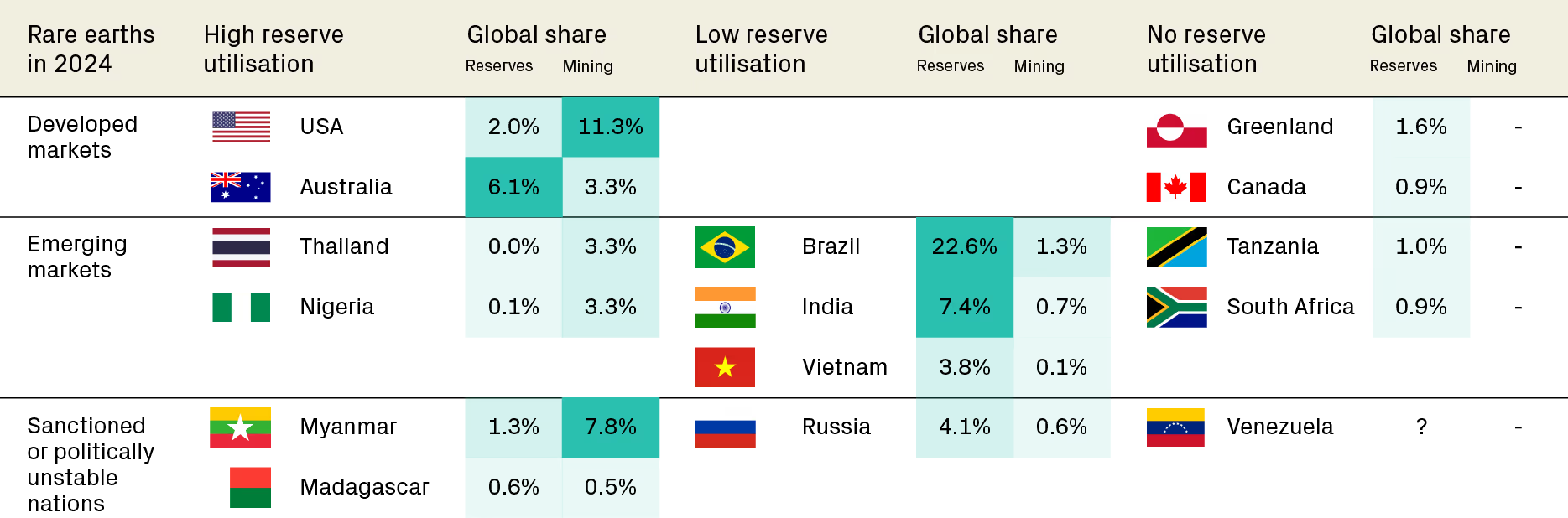

Despite China’s near monopoly of rare earths with >90% global share of refining capacity and 70% of mining production, it only accounts for 40% of global known rare earth reserves. Remaining reserves are distributed quite broadly across a range of developed and emerging markets, as shown in Table 1.

In developed markets, economic feasibility of rare earth mining is hindered by high labour and energy costs, strict environmental permitting, and high capital costs for the infrastructure required to access, process and transport minerals from increasingly remote deposits. As rare earth ores typically onlycontain between <1% and 10% rare earth oxide, vast quantities of material must be processed locally to avoid shipping unfeasibly large volumes.

Whilst easily accessible sites in Australia (e.g. Nolans Bore) and USA (e.g. Mountain Pass) are being built or expanded, others face an uphill battle. In Labrador, Canada, a mine proposed in Strange Lakes must transport ore by barge to a nearby processing facility built from scratch, then dispose of toxic and radioactive tailings containing arsenic, uranium and thorium in accordance with local environmental regulations, all whilst committing to protect the interests of local indigenous communities and wildlife.

In Greenland, access is even more challenging. Here, new roads and sea-docks require construction, and would only be accessible during summer months. Despite dozens of known rare earth deposits and the Greenlandic government’s attempt to attract foreign investment, private investors seem unwilling to contribute to the enormous infrastructure costs – only two mines (none rare earths) have been built in the past 35 years despite hundreds of known deposits.

In emerging markets, aside from political instability (Myanmar, Madagascar), mining investment has been held back by limited infrastructure and unfavourable governance. National strategies lack co-ordination, geopolitical non-alignment reduces need for onshoring, and financing structures are not conducive for domestic funding. Foreign investors are cautious due to economic volatility and examples of corruption, such as the unlawful granting of mining licenses in Vietnam.

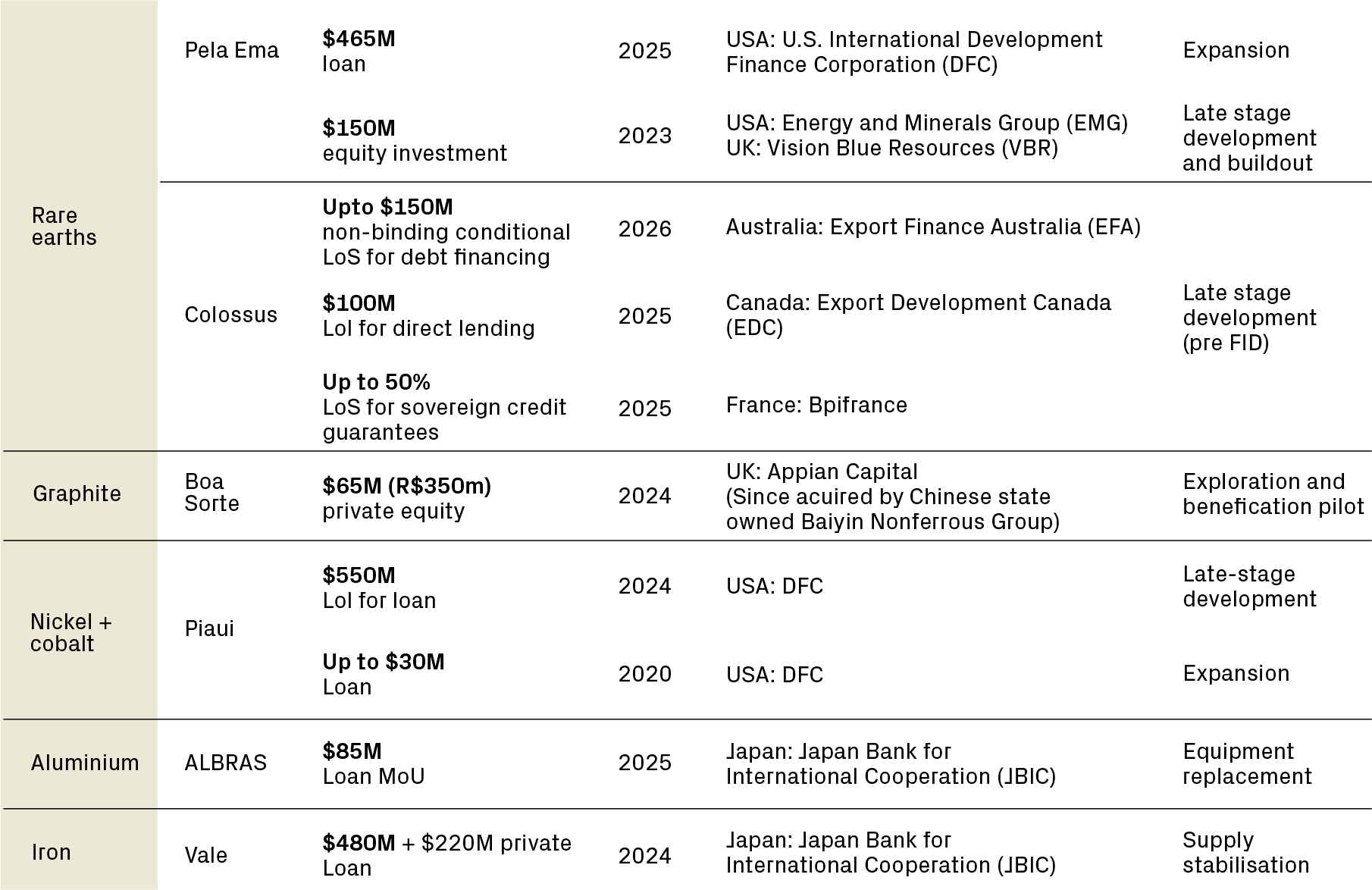

However, the outlook here is shifting as investors increasingly view emerging market risk as preferable to the growing geopolitical risk of reliance on China, driving more “friendshoring” investment. In Brazil for example, several projects have recently secured financing from a span of Western countries as seen in Table 2, even as China retains a strong foothold from historic financing and trade agreements – reflecting the Brazilian’s government’s willingness to partner across both sides of the divide.

The future will certainly see increased rare earths mining across diverse geographies to satisfy growing demand, but this alone will not be a silver bullet for supply chain diversification.

Refining is the key technology bottleneck where China dominates rare earth supply

Without refining ore to usable forms, more mining does not alleviate supply chain concentration. Refining is where Chinese expertise and decades of capital investment dominates.

Rare earths are chemically very similar to each other, and therefore difficult to isolate as individual elements from ore in which they are co-deposited. In the most common industrial method, solvent extraction (SX), plants can require many hundreds of sequential stages, each requiring a mixer settler (Figure 1), to reach >99% purity due to low selectivity of solvents towards specific elements. This requires high capital expense and sophisticated designs for control and cost reduction. Such investment is unappealing to private investors when payback period is long and future returns are volatile – a gap bridged historically in China by national strategic funding.

Refining requires deep technical capabilities in chemistry and process engineering, which are often unavailable in labour and infrastructure ecosystems surrounding profitable mines in emerging markets. To address this gap, increasing numbers of offtake and partnership agreements are being established between prospective mines in emerging markets and rare earth refineries in Europe, Australia and North America.

These partnership structures achieve synergies in capabilities, financing and operating costs, and represent an attractive long-term objective. However mines require time to establish and existing refining facilities face significant barriers to growth in the West:

- Significant upfront capital investment (several hundred million USD)

- High cost of energy and chemicals

- Large volumes of petrochemical solvents with high carbon footprint

- Environmentally responsible waste remediation and disposal

What’s more, trade agencies in emerging markets such as ApexBrasil are keenly aware of the economic advantages of refining in-country, and aim to stimulate national supply chains through initiatives and regulatory reform. Operators in the West should not comfortably rely on the ability to exploit cheap resources in these markets forever.

Refining companies need to include alternative sources and new refining technologies in their portfolio. The most interesting opportunities in rare earths today lie not in incremental improvements to conventional flowsheets, but in rethinking both feedstocks and process architectures in so-called ‘unconventional’ opportunities.

Circular economy: unconventionals requiring supply chain innovation

Circular economy narratives offer an appealing counterpoint to new mines amidst uncertain investment conditions. Critical minerals already exist in deployed products, so why not recover them?

Recyclable feedstocks are broad, but with a clear gradient of difficulty:

- Relatively accessible feedstocks such as wind turbine generators and EV traction motors and batteries, where critical mineral concentrations are high and isolated components are becoming available through organised end-of-life pathways

- Intermediate opportunities such as catalytic converters and electrolysers, which also present clear end-of-life collection pathways, but where critical mineral concentrations are lower amongst structural metals

- Highly distributed streams such as consumer electronic waste, where low concentrations and practicalities of disassembly are major barriers to implementation in typical recycling centres

End-of-life products offer material in guaranteed quantities, concentration, and ownership. But as previously discussed, rare earth recovery is costly and chemically intensive. Unless recovery can be bolted onto an existing operation, where logistics, handling, and disposal costs are already sunk to offset the processing costs, the economics quickly deteriorate without artificial pricing support.

Recycling is attractive for relatively accessible feedstocks, but the barriers are high for more disperse waste streams - likely prohibitively high with today's recycling technology.

A circular economy requires centralised processing facilities, with rare earths concentrated as much as possible at sorting centres via low-cost methods, e.g. advanced mechanical sorting. Business model innovation is also required. How to ensure sufficient waste standardisation for central processing? How to onboard sufficient waste providers to achieve a critical mass of rare earths? Does unpredictable end-of-life disposal add new volatility?

Mining tailings: unconventionals requiring highly selective extraction

Mining tailings are receiving increasing attention as an unconventional feedstock of rare earths: vast volumes have already been extracted, milled, transported, and stored within established industrial footprints; infrastructure and permits are already in place. Treating tailings as a resource rather than a long-term liability creates a structural opportunity to leverage existing assets while simultaneously addressing the cost and risk of waste disposal.

As a result, mining majors are actively partnering with technology providers to explore recovery from residues such as bauxite “red mud”, phosphogypsum, iron ore tailings, and coal fly ash. These materials are not attractive because of their grades – rare earth concentrations are typically low – but because recovery can be integrated with remediation, footprint reduction, or closure strategies. In this context, waste valorisation creates value by improving the overall economics of an operation, and is not simply focused on high absolute metal output.

However, tailings are unforgiving feedstocks. They represent material that was not worth extracting the first time around due to challenging compositions and low concentrations of valuable species - now also retaining traces of the legacy processing route. Due to the vast process volume, valorisation systems need to be deployable on-site to avoid high transport costs but can be restricted by available infrastructure and utilities.

As a result, tailings rarely suit conventional extraction approaches. Typical solvent extraction flowsheets for rare earth refining involve well over a thousand mixer settlers (~$100k per unit), owing to poor selectivity at each step. Such scales of capital and solvent consumption are difficult to justify for tailings where revenue is only a secondary value stream.

Technology innovation is unlocking the value of unconventionals

Selective chemistry to target specific fractions is key to reducing capital and operating costs of rare earths refining by reducing the number of separation steps required. Novel processes can concentrate the rare earths stream prior to traditional solvent extraction or replace solvent extraction altogether.

Many of these solutions are modular by nature, making it possible to design smaller profitable systems that require less investor “leap of faith”. This route-to-market strategy supports real-world operational maturity with limited capital exposure, whilst allowing capacity to scale progressively as confidence in both the technology and the economics grows.

Designing early to integrate with existing balance of plant, equipment supply chains, and operational workflows is critical to industrial adoption. Investors today are increasingly looking for scalability and bankability – complexity cannot simply be deferred to a future time or up/downstream process.

For example, a process that requires an existing upstream operation to use a new solvent faces a far larger leap of faith than one which can utilise the current solvent; likewise for novel equipment or reagents that require novel manufacturing methods, compared to those which can utilise proven techniques.

Emerging techniques for rare earth extraction

Here we discuss five emerging techniques with strong momentum. These compelling approaches for unconventionals all have the potential to accelerate learning at scale, simplify flowsheets, and fit cleanly alongside existing operations.

Ionic liquid (IL) extraction

Uses classic solvent extraction principles but instead uses ‘designer’ solvent molecules that are tuned for selectivity towards specific elements. Ionic liquids are simply salts that are liquid at ambient or slightly elevated temperatures, often with at least one organic component. Costs today are high but largely due to low demand. Use of ionic liquids keeps a recognisable flowsheet while enabling better selectivity for fewer separation stages.

Continuous ion exchange (CIX)

Perhaps the most proven path for pre-concentration - the process stream is flowed through a resin containing sites on its surface that are functionalised by speciality binding molecules (e.g. chelating, strong acid or strong base groups). Target elements bind to these sites under normal process conditions and detach (elute) when flushed with eluent. Different binding thresholds can enable sequential elution of specific species in different eluents. Continuous flow is achieved via moving resin bed (e.g. carousel) configurations – intensifying throughput compared to traditional batch configurations. Using hardware and control philosophies already familiar to major operators is a clear operational advantage.

Biological methods

Techniques using biomolecules with exceptional affinity for target elements. This can be in ion exchange format (e.g. resins functionalised with the protein lanmodulin), or it can be via the uptake of rare earths by microorganisms in stirred tank reactors, or by plants from soil. Relative to other chemical methods, biological routes enable lower energy intensity and milder conditions that can help to offset costs when profit margins in unconventionals are sensitive. As protein structures are sensitive to composition and temperature of solution, separation of target ions via sequential eluents can be highly selective.

Supercritical CO₂ (sCO2)

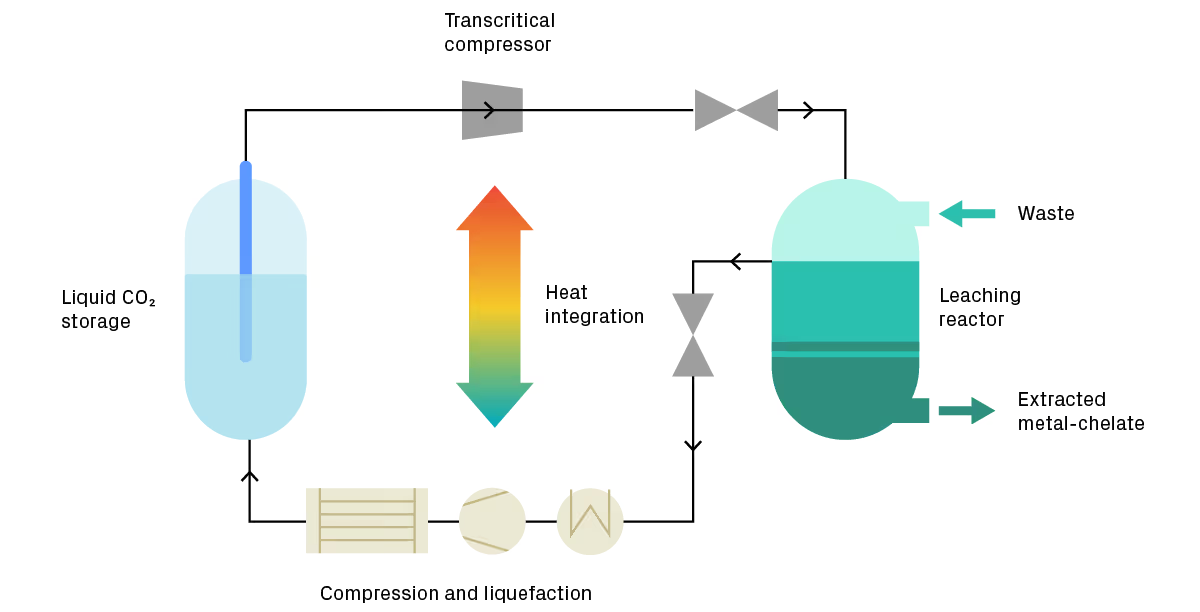

This method of rare earth extraction uses a blend of CO₂ and selective binding agents in supercritical fluid state as the solvent with which to extract target elements. Elevated pressure accelerates leaching from solids, then depressurisation to remove CO2 as gas allows simple separation of concentrated product. The CO2 solvent is more reusable and less expensive and hazardous than traditional extraction solvents. Transcritical compressors are increasingly available due the emerging use of sCO2 as a next-generation refrigerant in commercial and industrial buildings.

In the block flow diagram in Figure 5, liquid CO2 is loaded with a co-solvent that is selective towards the target element, and solid material for extraction (e.g. waste) is loaded into the leaching reactor. The liquid CO2 is compressed to a supercritical state and fed into the leaching reactor, where the co-solvent extracts the target fraction at high temperature and pressure. After extracting, the leaching vessel is depressurised. The CO2 becomes gas state, separates from the leachate, and is re-compressed to liquid CO2 for storage. The residual co-solvent containing the extracted ions (e.g. as a metal chelate) remains in liquid state and can be easily separated from the solid via the bottom of the leaching reactor.

Polymer inclusion membranes (PIMs)

PIMs are thin polymer films with embedded selective extractant molecules (‘carriers’) that selectively transport ions across the membrane. The carriers can be derived from traditional selective solvents or novel ionic liquids. The value proposition is process intensification: high rates of extraction are enabled by maintaining a high concentration gradient over a thin membrane, whilst simultaneously avoiding large inventories of expensive, hazardous, carbon-intensive solvent.

At the feed side membrane surface, target ions selectively bind to a carrier molecule to form an adduct (ion-carrier pair). At the stripping side membrane surface, the adduct dissociates, releasing the ion into the stripping solution. The stripping solution composition is chosen to favour this dissociation. High adduct concentration gradient over a thin membrane encourages fast diffusion from feed to stripping solution, which can be accelerated by plasticisers in the membrane.

PIMs are more selective and more robust compared to other membrane methods, and contain far smaller inventory of expensive selective carriers than non-membrane methods.

What is the best route to resilient critical minerals supply?

Critical minerals are not constrained by geology. They are constrained by how intelligently we design systems to extract, refine, and recycle them under real economic, environmental, and geopolitical conditions.

Across rare earths, the pattern is consistent. Ore bodies are accessible but refining dominates value and risk. Circular supply is attractive, but only when feedstocks are chosen realistically and integrated into viable business models. Mining tailings offer scale and operational alignment, but only to processes that are designed to accept low grades, variability, and thin margins from the outset.

The future of critical minerals will not be defined by a single breakthrough technology or a rush to replicate China’s legacy infrastructure. It will be shaped by selective recovery, modular deployment, smarter process architectures, and a willingness to innovate at system level rather than optimise in isolation. Unconventionals will play a critical role in that transformation.

Technologies that reduce complexity instead of relocating it, and that can prove themselves economically in small steps before expanding, offer a more credible path forward in volatile markets. They allow industry to move faster, take measured risk, and build confidence incrementally, without betting entire balance sheets on uncertain futures.

For organisations willing to treat critical minerals as a process and systems challenge, rather than a resource shortage problem, the opportunity is real. Abundance already exists. Turning it into advantage depends on how thoughtfully it is unlocked.

How can TTP help clients develop novel process technologies?

At TTP we are developing, de-risking and scaling up novel process technologies to enable a sustainable future of energy and materials. From discovery to deployment, our multidisciplinary team is ready to help accelerate the progression of your technology. If you need an experienced partner that combines robust risk management with fast-paced and adaptable innovation, get in touch today.

.avif)